In tandem with today’s resurgence of vinyl records, the physical pressing of vinyls in Kenya’s capital city of Nairobi, not only shaped the country’s historical musical soundscape but also made space for a melodic communion that danced upon the confines of imperial borderlines.

From the early 1920s, commercial recordings of East African musicians were released and pressed internationally under labels like His Master’s Voice (HMV), Columbia, Pathé, and Odeon. The beginning of the 1930s brought together the merger of these four labels under one company, EMI, and in 1947, Jambo Records became the first independent East African record label that was established in Nairobi. Started by two British men, Eric Blackhart and Dr. Guy Johnson, just three years prior to Kenya’s Mau Mau anti-colonial movement, the songs created under the Jambo Records label would be sent to England to be pressed by Decca Records and then shipped back to Kenya for sale. After an approximate ten year existence, the label was sold to Charles Worrod who had previously worked for Gallo Records in South Africa. The purchase of Jambo Records included the rights to recordings that had been made under the label and one of the key songs that was acquired through this deal was “Malaika.” The song carries within it a charged history, with its theme said to have been originally composed by Kenyan musician Grant Charo and with it having been subsequently covered over time by musicians like Miriam Makeba, Boney M, and Angelique Kidjo.

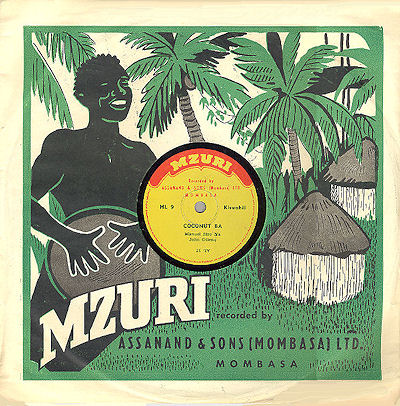

Worrod then reconstituted Jambo Records into Equator Sound Studios with the core house band – the Equator Sound Band, previously known as the Jambo Boys Band – originally consisting of Fadhili William, Daudi Kabaka, two Zambians, Nashil Pichen and Peter Tsotsi Juma, and Frida and Charles Sonko from Uganda. Against the backdrop of Kenya’s independence struggle, the 1950s ushered in the presence of East Africa’s first, physical vinyl pressing plant. Started in 1952, the plant named East African Records Limited, was situated in Nairobi and at the beginning was run under the African Ground Cotton Company. Recruited from Denmark to oversee the plant, Otto Larsen, a studio engineer, settled in Nairobi and subsequently began to travel across East Africa. He recorded a vast range of genres from taarab, to the emergent sounds of benga plucked on acoustic guitars, stylistically and rhythmically drawn from traditional nyatiti music. With vinyl production now situated in the region, East African Records Limited helped morph Nairobi into a vital musical hub. By the late 1950s there were more than 40 independent record labels such as Mzuri Records owned by Assanand & Sons Ltd, which was originally started in Mombasa, and African Gramophone Service (AGS) and Capitol Music Store (CMS) in Nairobi. These, among other labels mapped across the East African region, became a home for the sounds pressed in wax and distributed by the plant.

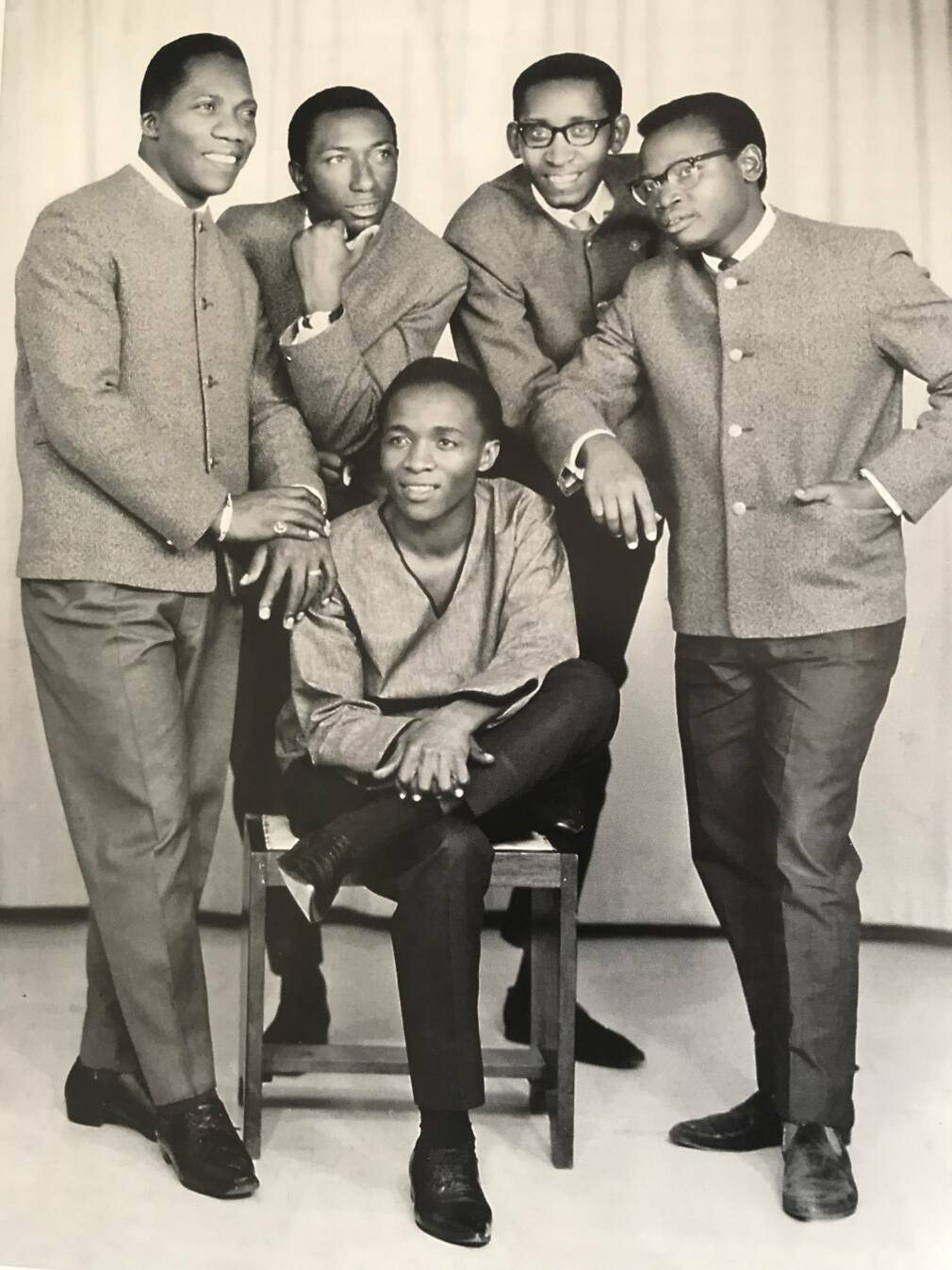

The 1960s and 1970s, often referred to as Nairobi’s glittering epoch the city became the ultimate recording epicenter. Individual musicians and bands from Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, DRC, Uganda, and Tanzania would arrive in Nairobi principally to record, but would also seize the opportunity to perform at a host of vibrant venues and clubs. The presence of South African cabaret band, Lo Six, Zambian band, Mosi O Tunya, Tanzanian band, Jamhuri Jazz, and Congolese bands such as Orchestre Baba National and Les Mangelepa, all left an indelible mark on Kenyan musical traditions that stretched beyond music. South African kwela music helped shaped the African Twist, a genre pioneered by Kenyan musicians Daudi Kabaka and Isaya Mwinamo, Congolese rumba sweetly influenced the works created by bands such as Simba Wanyika found in their distinct, slithery guitar riffs, while the striking outfits of Mosi O Tunya, accompanied by their psychedelic, electric rock, boosted both the stylistic dress and melodic output of the Kenyan group, the African Heritage Band.

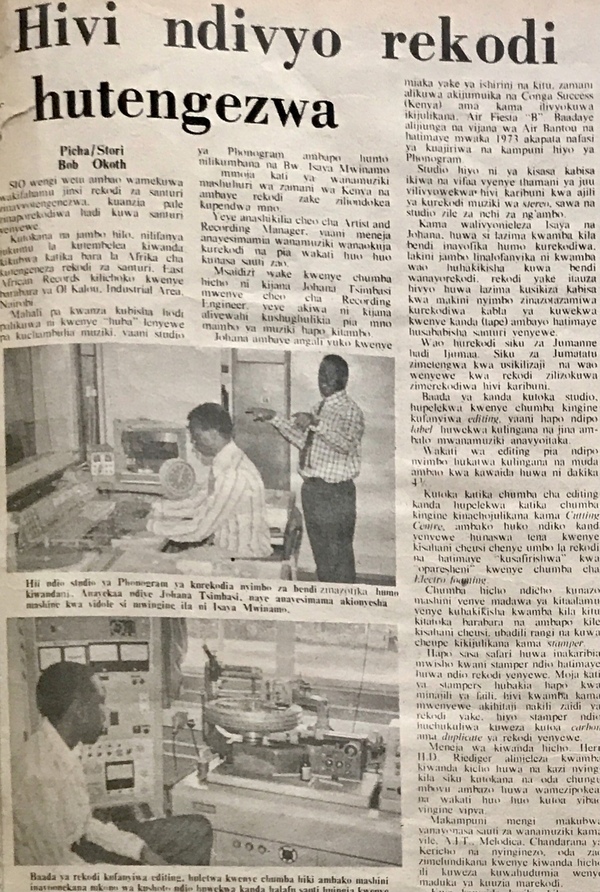

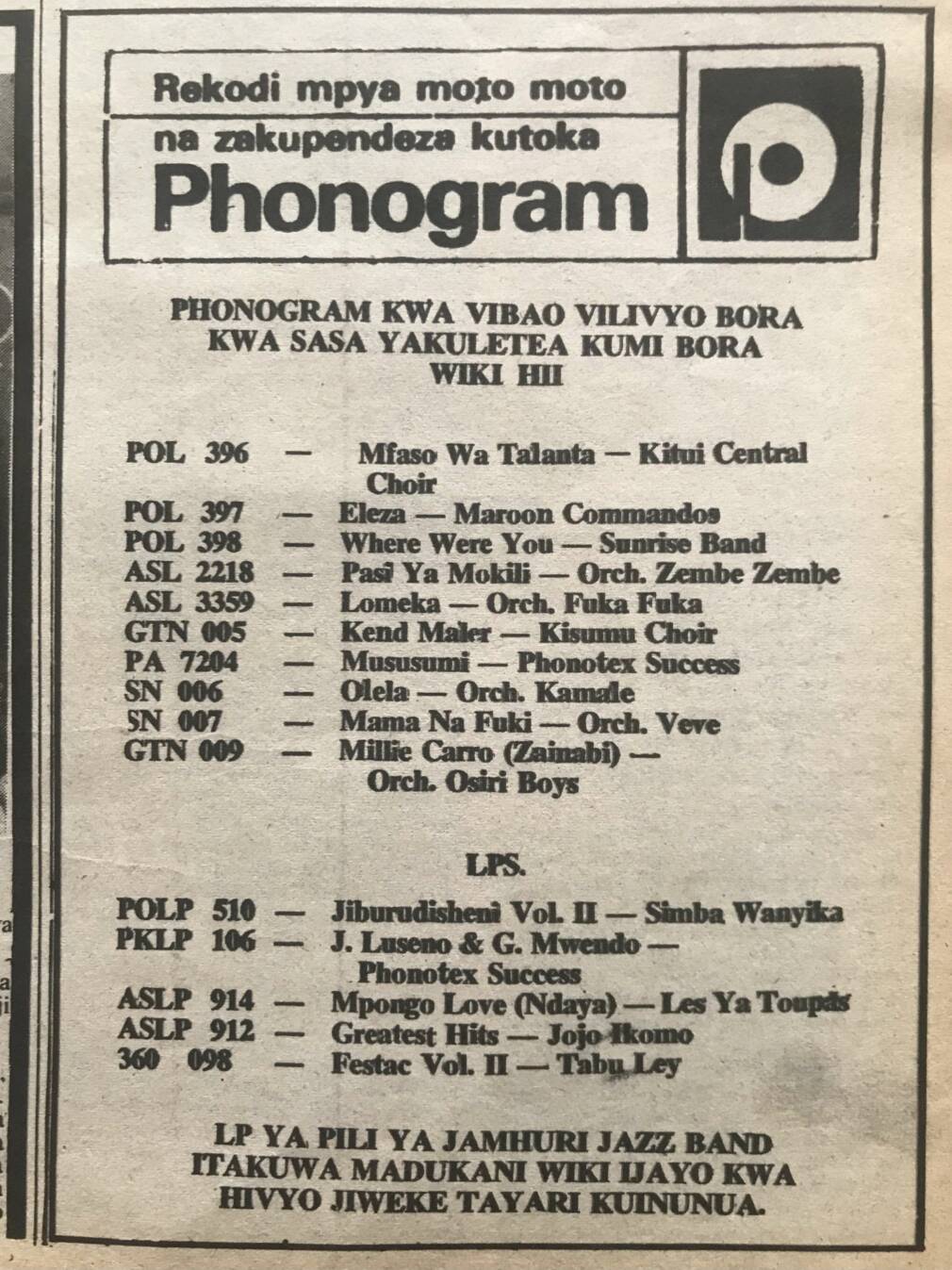

During this period, East African Records Limited transferred ownership and became a subsidiary of the multinational, Polygram. The plant was located in the city’s industrial area and it pressed a total of around 62,500 records weekly, with this number increasing to around 105,000 records weekly during the December holiday period. In the late 1970s, the company Sapra set up a vinyl manufacturing company. Altogether both Sapra and East African Records Limited registered a daily output of 22,000 records which would be exported to countries such as Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Malawi. These plants also embalmed in wax the music of Ethiopia, Somalia, and Seychelles. Nairobi functioned as an epicenter for record exports with the city’s industrial area and downtown River Road section being its focal point. Each newly minted record release was announced in local newspapers like the Baraza so that people would be able to stay on top of, “rekodi mpya moto moto,” the newest and hottest releases.

The 1980s came with the shift from vinyl to cassette and also with the birth of disco which predominantly came with the move away from experiencing live performances at clubs, towards the experiencing of music through the crafted mix of a DJ. An economic slump, rampant piracy aided by the ease with which music on cassette could be illegally reproduced, and changes in musical consumption meant that the vinyl pressing plants soon became redundant and succumbed to closure. This shift was also reflected in the dampening of musical convergence across borders with political tension flaring between Kenya and Tanzania and with Kenya’s Department of Immigration choosing to decline the work permits of musicians who had resided in the country for many years.

The 1990s onwards carried with it a shift in the production and interaction of music, greatly influenced by the experiencing of music digitally. In the cyclical nature of history, the resurgence of music heard through the crackles and static hum of vinyl is joyously and persistently beckoning through. Presently, Kenyan artists such as Maia & the Big Sky, Blinky Bill, and Nyokabi Kariũki offer vinyls to accompany the digital presence of their work. The newly issued Insha vinyl compilation celebrates Kenya’s past and present through the collective works of different electronic musicians brilliantly expanding sonic worlds. All these records are pressed internationally as the Nairobi pressing plant that once took up central sonic, economic, and physical expanse in East Africa no longer exists. Despite there being no immediate plans discussed to awaken the vinyl pressing industry in Kenya, there still holds a special delight in being able to dance between time and space through the above contemporary releases. Holding gently the aforementioned cyclical nature of history, maybe the return of the pressing plant stands wrapped in a mist replete with hope.